The Cleaner, the vast retrospective of Marina Abramović’s work, is finishing its European tour two years after it kicked off – in Belgrade, her hometown, and the place she has by and large shunned since leaving it as a young artist over 40 years ago. The exhibition is housed in the Museum of Contemporary Art, a recently renovated gem of mid-1960s brutalism, sitting comfortably at the edge of a sprawling park at the majestic confluence of Belgrade’s two rivers. Its seemingly stark shapes belie the lightness of form that reveals itself on the approach.

We are greeted by the recording of blackbirds coming from the nearby trees, only to be overwhelmed by the looped sound of machine gun fire on entry – an early 1971 sound piece, and a bold opening choice in a country whose uncomfortable legacy of civil war still lurks just below the surface. Once inside, the machine gun gives way to moans and cries, coming from the first floor, where black-and-white films of her early performances are being played at full volume.

It’s a relentless assault on the senses, softened by the unexpected warmth of the museum’s well-proportioned interior. Clever lighting and sound engineering make the exhibition feel oddly intimate, despite the intensity of sounds and the monumental size of the stage sets and canvases on which the images of her performances are being projected. The visitors remain cocooned in the dark, protected from their own self-consciousness, undisturbed by each other’s presence, yet close enough to exchange quick glances in case they need a bit of reassurance.

This cocooned privacy within close reach of others is essential. For Marina Abramović is a master of self-harm as an art form and there is violence in all her works, even when they invoke the greatest tenderness – sometimes direct and self-inflicted, sometimes outsourced to the audience, always as a humming emotional soundscape in the not-so-distant background.

I met Abramović through her later works, but it is her first performances that I still find the most emotionally involving. Conducted in the early 1970s, many of them in Belgrade, they are a series of increasingly risky acts in which she tests her own bodily endurance, as well as the emotional and moral fabric of her audience. From jabbing a knife between the splayed fingers of her hand, to losing consciousness and nearly asphyxiating while lying in a petroleum-drenched burning star, to passing out in front of an industrial fan, carving a five-pointed star on her abdomen, or ingesting strong psychotropic medications as a performative act, she entered the artistic world by setting the emotional bar high – and with it also the moral stakes.

Nowhere is this more visible than in Rhythm 0, often thought of not just as her most radical piece but also as one of the most significant works in the history of performance art. Rhythm 0 took place in 1974, in Naples, and it involved Abramović standing still while the audience was invited to do to her whatever they wished, using one of 72 objects she had placed on a table. These included a rose, feather, perfume, honey, bread, grapes, wine, scissors, a scalpel, nails, a metal bar, a selection of knives, chains and axes, and even a gun loaded with one bullet. The wide-shot video of the performance is played in a quiet niche of the exhibition behind the desk containing the same 72 objects. In it, the men – for the audience is vast majority male – cut her skin and her clothes, expose her breasts, pour oil on her head, write slogans on her naked torso, and watch her as they smoke, laugh, chat. The camera occasionally focuses on her eyes, filling with tears, though never quite overflowing. The accounts of the performance say that once the allocated time was over, Abramović walked into the audience seeking to engage them and talk about what they chose to do and why. They all fled.

The statuesque, striking woman in those acts somehow manages to come across as poised and possessed at the same time. Her performances were consistently risky, potentially life-threatening. Her body was the tool, the harm she exposed it to a constant invitation to her audience to test the moral fibre they too were made of. As I walk through the grainy recordings of these emotionally and physically radical early acts, I feel caught in the spectacle, an innocuous observer and judgmental inflictor of harm at the same time.

I can’t help but think how out of sync this city and its greatest contemporary artist were, perhaps from the start. As long as I can recall, Belgrade’s main currency of social interaction was irony, and appearing not to care was the only thing that strict social codes allowed a cool urbanite to visibly care about. In the good times, this could have been a cultural trait as exasperating as it was charming – but the same spirit turned out a less reliable guide for Belgrade’s intellectual establishment’s response to the emerging nationalism in the 1990s. Irony and relativization proved unable to offer any meaningful defence against the encroaching malignancy, and were quickly coopted in the discursive toolbox of Serbia’s postmodern nationalism.

Walking through these rooms I find not a shred of Belgrade’s iconic irony in Abramović’s work. The artist, the vast expanse of this exhibition says, is earnest. And not afraid to show it. It is this utter lack of irony that has often made me feel uncomfortable around Abramović’s work – and often made her a target of criticism or ridicule. Just last year, in Seth Meyer’s mocumentary episode “Waiting for the Artist”, Cate Blanchett pulled off a brilliant send-up of performance art in general – and of Abramović in particular – imbued with the spirit of the 11th commandment of our self-conscious times: Thou shalt not take thyself too seriously.

But as I walk through the exhibition, another kind of disquietude starts setting in. Canvas after canvas, performance after performance, Abramović’s occasional public slippages into only too human errors of pretentiousness or poor accounting are balanced out by the sheer weight of her artistic legacy.

The exhibition successfully captures the softening of her methods. Her body remains her main tool, and she keeps exposing it to distress and to the self-conscious gaze of her audience, but not to direct self-harm anymore. Performance after performance, deep into her 60s and 70s, Abramović continues to identify and explore the hardest questions of the human condition in our uncannily disconnected times – the troubling resurgence of identarian violence, as in her Balkan Baroque; increasing loneliness and (self) isolation, as in The Artist is Present or The House with the Ocean View; or lack of endurance and our shortening attention spans in Counting the Rice. Whatever the issue, she continues to approach it with gravity, fixatedly, seemingly oblivious to the critics’ growing disapproval of her absence of ironic distance.

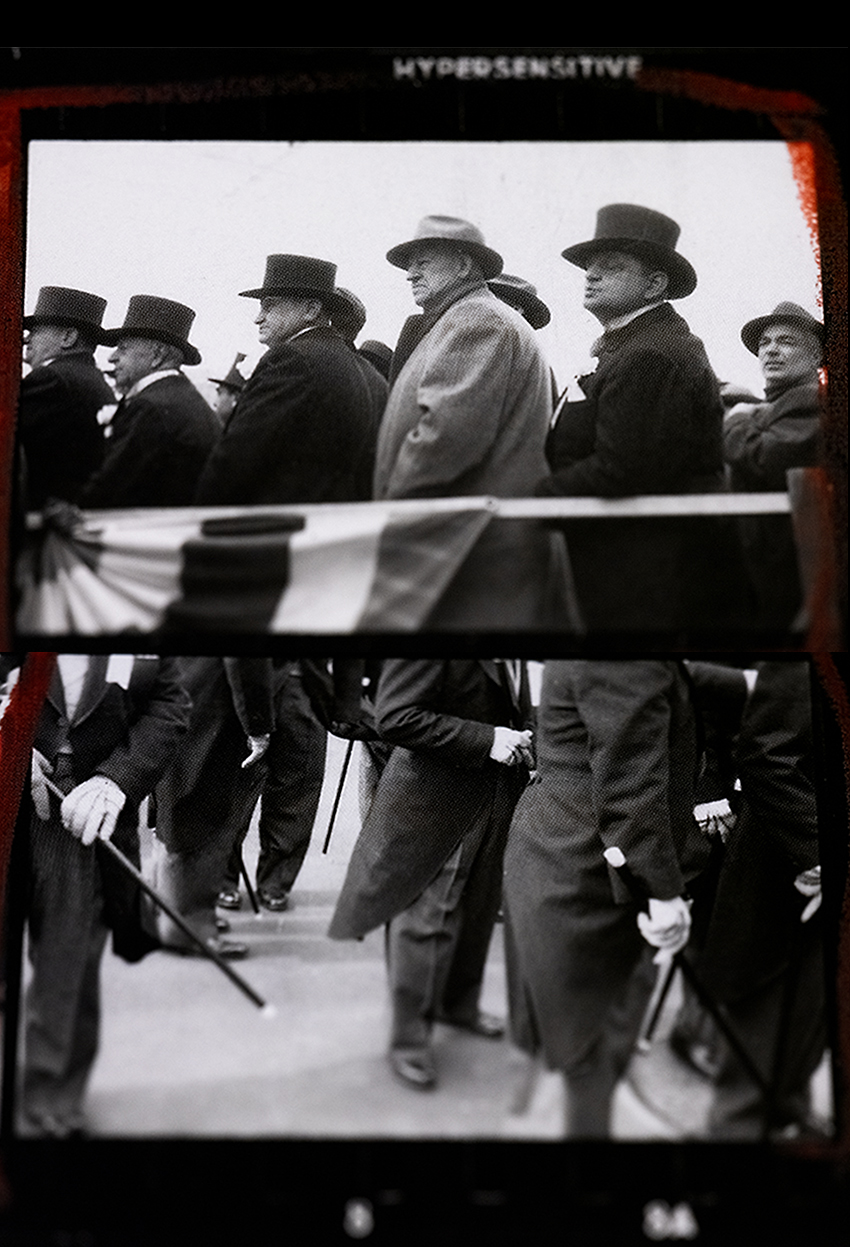

Somewhere in the middle of the exhibition I stumble upon a much smaller work, called Heroes. It is a black-and-white video of Abramović on a white horse holding the flag of the former Yugoslavia. Against the wall on which this almost-still image is being projected, there is a small glass cabinet, containing the mementos of her parents’ heroic World War II past – old Partisan IDs, formal documents recounting the events that earned them the heaps of medals and decorations lying on the grey-felted lining, including the prestigious silver medal given to those who joined the Communist-led fight against Nazism in the very first days of the war.

The stern faces of Abramović’s high-ranking Partisan parents, driven by a belief in ideas and values beyond themselves, look at the visitors from black-and-white photos in this collection. These were the creators of an imagined country of equality and dignity and a classless good life, driven by merit, hard work and uncompromising moral positions – often also painfully applying the same unyielding principles on their children, as Abramović herself frequently recounted.

Here, in front of this display, Abramović is miles away from the pretentious artist driven by New York fads that Blanchett so hilariously parodied. It is in this tiniest of her works that I find what is to me the most significant clue to the person that drives the art – for there is a grain of that earnestness in myself, my sister, my cousin; all of us carefully negotiating this emotionally-loaded space at safe distance from each other.

Abramović is the first and we, I realize, the last of the generations born in this country whose public and personal lives were shaped by the revolutionary cohort born in the 1920s – the people who fought and won the war, and then got to mould the broken world to their ideals.

Unlike in the rest of Eastern Europe, communism in Yugoslavia was not an ideology imported on Soviet tanks – it was a homegrown grassroots movement, much like the one in Italy, Spain or Greece. But unlike in those countries, here it managed to stay in power, tactically accepting Soviet backing, but also quickly renouncing it and pursuing its own idea of a functioning and comfortable society based on ideals that we would today call multiculturalism and social justice – though short of the full set personal freedoms.

But while the content of ideology is not unimportant, what matters even more is that we had people in our lives who time and time again took conscious risks for issues that they firmly believed were of greater value than their lives. They rocked us on their knees, took us to school, for walks or to the zoo, bought us ice-cream and told stories that shaped our views of the world. Some of them may have also had an ability to laugh at themselves, but there was an unquestionable firmness to them, borne out by the totality of their life choices: that principles, values and ideas could be worth living by and dying for.

Expressed in the radical choices of her tools, and the gravity of her recurring themes, the voice of that generation comes loud and clear through Abramovic’s art. In this dimly-lit space, in this buzzing city of great (and sometimes also greatly damaging) irony and capacity for relativization, her persistent earnestness suddenly feels both like a remnant of a bygone era and the most subversive of her performances; an uncomfortable reminder that perhaps not everything is that relative.