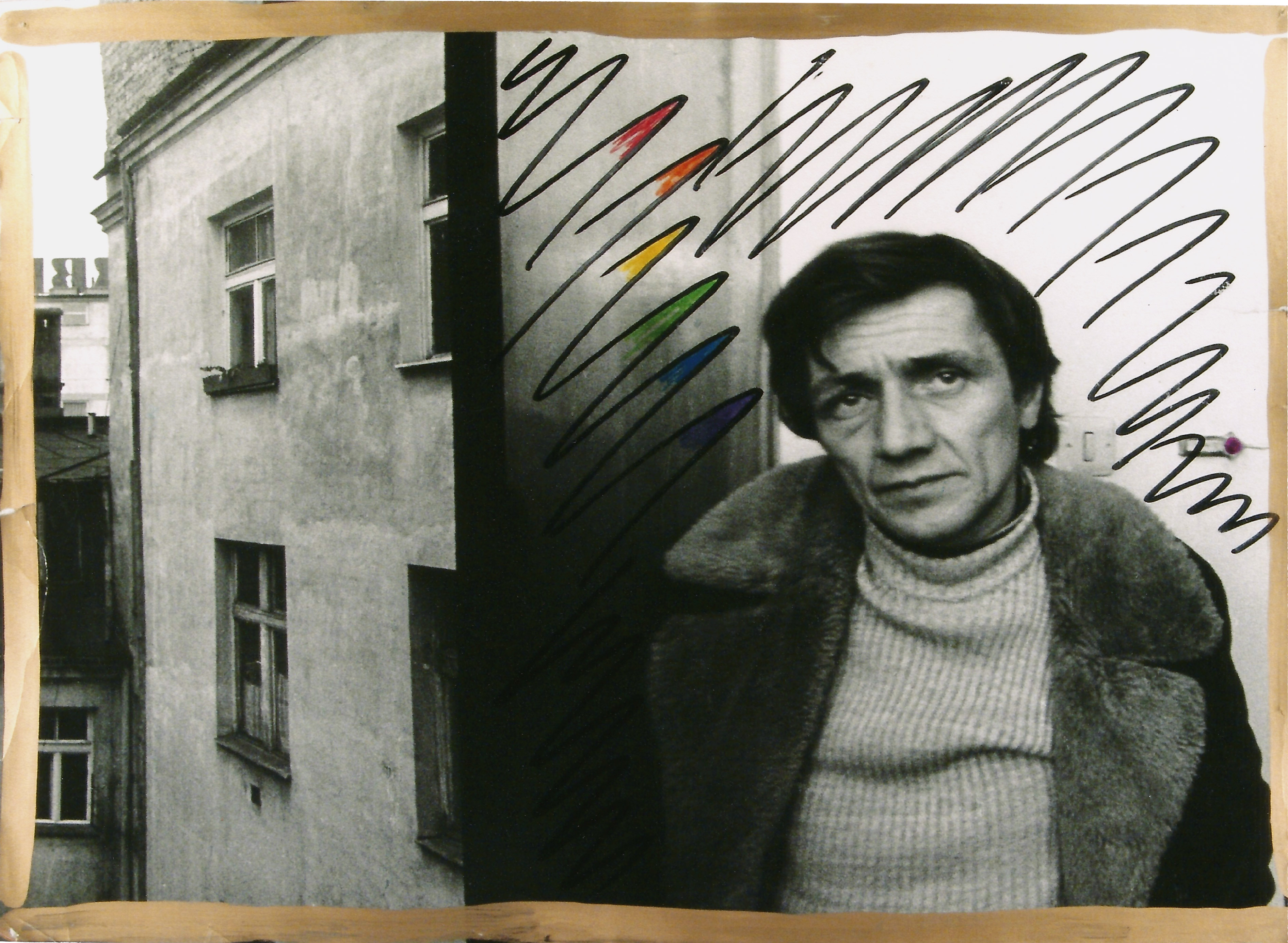

Have you heard of Mela Muter? Here is the story of a Polish-Jewish painter who was active in difficult times. She studied art in academies and under the tender eyes of authority figures, had affairs with Leopold Staff and Rainer Maria Rilke, and died alone.

Maria Melania Klingsland, later known in the art world as Mela Muter, was born on 26th April 1876 in a Warsaw tenement at 28 Leszno Street, Apartment 12. She was the second of five children of Fabian Klingsland and Zuzanna, née Feigenblatt. Melania’s parents belonged to a group of rather wealthy Jews, which is also attested by the location of their home on the southern side of Leszno Street, at the time known as ‘Ujazdowska Avenue of the Jewish district’. Fabian Klingsland, born in 1838, owned a department store in the city centre, at 129 Marszałkowska Street. Mela’s mother, 10 years younger than her spouse, came from from the Muszkats, a famous family of rabbis and kohanim. The Klingslands spoke Polish at home and supported Polish attempts at regaining independence. Fabian tried to be a patron of young writers. Władysław Reymont and Jan Kasprowicz were among the guests at his home. Every now and then Leopold Staff also popped in, who was to play an important role in Mela’s later life.

The Klingslands’ children, on top of conventional education, were also fostered by German and French governesses. Melania, due to her weaker physical constitution, had a nanny too, who whispered Polish prayers into her ear when putting the girl to bed. Fabian’s and Zuzanna’s daughter stood out with her beauty and demonstrated exceptional sensitivity and artistic talent. In 1982, she graduated from high school and started taking private drawing as well as piano lessons from a prominent teacher, Professor Jan Kleczyński.

In 1899, Melania married Michał Mutermilch, two years her senior. From an early age his passion was literature. He tried his hand at novels, playwriting, translating and working as a press correspondent. When he became involved with Mela, he also began writing reviews of art exhibitions. Like many educated Jews in those times, he was a member of the socialist movement. He supported the emancipation of women. It was thanks to him that this same year Mela enrolled into the School of Drawing and Painting for Women. The place, established in 1892 by the painter, singer and composer Miłosz Kotarbiński, was – apart from Adrian Baraniecki’s courses for women and Tola Certowiczówna’s school in Kraków – the only place in Poland where it was possible for women to study art. The Fine Art School in Warsaw was closed down on the Tsarist authorities’ orders and remained closed until 1904, while the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków started officially accepting women only from 14th December 1918.

The world in miniature

Andrzej, the first and only son of Melania and Michał, was born in 1900. A year later, the Mutermilch family moved to Paris. What attracted them was the chance for Mela to study at the best art schools and the prospect of an interesting life. The whole endeavour was financed by Fabian Klingsland, who was very approving of his daughter’s artistic development. For thousands of young, ambitious, sensitive people from across the world, Paris at the time was “the universe in miniature”, as Zygmunt, Mela’s younger brother called it, when he later joined the Mutermilchs in Paris. It’s worth knowing that in the years 1890-1918 – as mentioned by Karolina Prewęcka, author of Mela Muter’s only biography to date – about 700 Polish artists came to France, including about 200 women. This number should not be a surprise, since at home all that awaited them was bearing children and serving men.

While in Paris, Mela started attending a private art school called Académie Colarossi at 10 Rue de la Grande-Chaumière. It was a school with traditions, among its students were the famous Camille Claudel – involved with the sculptor August Rodin – as well as the renowned Poles Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Mehoffer. Eugeniusz Zak and Wacław Żaboklicki also studied there, and a bit earlier, Bolesław Nawrocki – the son of the owner of the brickworks in Pabianice, who painted the first, small portrait of Mela in 1903 – was one of its students. Mela reciprocated much later, in 1965, by painting a portrait of his son, which was in fact her last finished work.

Mela Mutermilch rented a studio at 65 Boulevard Arago in the district of Montparnasse. Right next door, at number 49, was Olga Boznańska’s atelier. The famous artist taught for a while at Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Mela liked popping in there, because of Boznańska’s ‘drawing in five minutes’ lessons. That was how long a model could stay in one pose. For the young mother who didn’t want to abandon her parental responsibilities, this was the perfect way to learn how to draw. But nothing could compare to direct contact with an artist who was more contemporary in spirit. Mela found that kind of master in Władysław Ślewiński, whom she met during summer holidays in 1901 near Pont-Aven in Brittany. From that point onwards, she returned to the region many times, and its landscape and local people became frequent themes of her paintings from the first decade of the 20th century.

Exhibitions, affairs…

The 26-year-old painter started exhibiting her works, and did it with great panache. In Paris, she took part in the Salon of the Independents, the Autumn Salon and the Salon des Tuileries. Moreover, her paintings could also be seen at exhibitions in Kraków and Lwów. In Warsaw, The Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts organized her first solo exhibition in their new building at Małachowskiego Square, with 20 of her paintings on show. In later years, she had two more individual exhibitions there.

In the autumn of 1902, Leopold Staff arrived in Paris, who – as we remember – used to visit Mela’s father at home when she was just a teenager. Mela and Leopold found each other in the huge Parisian social melting pot and unexpectedly fell in love. Even though their affair left no hope for a life together, since she was a mother and a wife and he was a free spirit, it still lasted until the winter of 1907. They broke up most likely when Mela’s husband caught the lovers during a rendezvous in Zakopane. He gave her an ultimatum then: either him or Staff; she had six months to decide. In the end, after spending some time on her own in Florence, Mela decided to go back to her husband, but their marriage was already practically dead. To mark the separation, from 1916 onwards she started signing her paintings as ‘Mela Muter’. They divorced formally four years later. Portrait of a Poet was all that was left from the relationship with Staff. Mela painted it in 1903. In the background of the painting, she placed the famous death mask of ‘L’Inconnue de la Seine’ who – according to some – looked a bit like the artist herself.

Meanwhile, in 1904 in Paris ‘the other Leopold’ appeared, who soon became Mela’s closest companion and a friend of the Mutermilch family. He was Leopold Gottlieb, the brother of Maurycy, the famous painter who died young. Before coming to Paris, Leopold, just like his brother, studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, and then at the Munich Academy. Gottlieb became so close to Mela that sometimes they created paintings together, such as their 1910 work entitled Pieta. Up until today, experts struggle to tell one from the other, despite signatures. Leopold remained close to Mela up until World War I. When the war broke out, he was in Kraków, which he fled to join Józef Piłsudski’s Legions. But even earlier, in June 1914 in Paris, he fought a duel with another friend of Mela’s, the painter Mojżesz Kisling, known as the ‘Prince of Montparnasse’. According to gossip, he was attempting to defend her good name. In reality it was probably down to political differences. Either way, the event was captured on film and we can watch a snippet of the then world and its customs.

Mela and Girona

According to Mela herself, the breakthrough event was her exhibition in Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona in June 1911. The owner of the gallery, Josep Dalmau y Rafel, was a promoter of new developments in art, well-known in Catalonia. Artists such as Picasso, Miró, Dalí, Matisse and Duchamp exhibited there. Mela Mutermilch presented 33 paintings, much loved by the local audience. A year later, surfing a wave of popularity, Dalmau organized an exhibition of 15 Polish artists chosen by Mela. Altogether there were 136 works of art, including paintings by Leopold Gottlieb, Olga Boznańska, Roman Kramsztyk, Tadeusz Makowski, Józef Pankiewicz and Eugeniusz Zak, whose drawing also appeared on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. The introduction to the catalogue was written by Michał Mutermilch, who also gave a lecture about the influence of the political circumstances on art and literary life in Poland during a conference accompanying the exhibition in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Barcelona.

From the beginning of April until June 1914 Mela was again in Catalonia, this time in Girona, at the foot of the Catalan Range. That’s where she worked on a series of new pieces. 17 paintings were created, including seven watercolours, which, accompanied by three pieces on loan from the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona, were exhibited locally in the Athenea Association gallery. The exhibition took place towards the end of May of the same year. Mela’s art left a lasting impression on art lovers in Girona – so lasting, in fact, that at the turn of 2018 and 2019, a posthumous exhibition of her work was organized in the local Museu d’Art.

Splendour and crisis

Mela spent the years before World War I with her son Andrzej, partly in Brittany and partly in neutral Switzerland. Her husband Michał volunteered to join the French army. At that time, Mela practically stopped painting portraits and instead focused on small-size still lifes. The exception was a portrait of a certain Różycki, entitled Blind Soldier. Towards the end of the war, in 1917, Mela met Raymond Lefebvre, 17 years her junior, the main figure in the then French socialist movement, co-creator of the group of left-wing intellectuals ‘Clarté’, as well as of the well-known newspaper L’Humanité. Soon after, Raymond became another great love of Mela’s. She had far-reaching plans for him. Because of him, she made every effort to get a formal divorce from Mutermilch. In July 1920, Lefebvre and two other French comrades travelled without passports to Russia to take part in the Second World Congress of the Comintern in Petrograd. Just when it seemed that he could finally start his life with Mela, he and four other men drowned in the Barents Sea during an attempt to leave Russia. The details of his death still remain unclear.

The first half of the 1920s brought a lot of suffering to Mela: in December 1922 her father died, and during the night of 10th December 1924, her 24-year-old son Andrzej also died. Supposedly he drowned while taking a bath. In the meantime, in 1923, Mela, just like many of her artist friends of Jewish origins, was baptized in the Catholic Church. The real consolation came in the spring of 1925 in the form of a new romantic infatuation. The object of her love interest was the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. They met during a tea at the singer Marie Dubas’s, known for her variety performances at the Casino de Paris. Mela and Rainer started an affair, mainly carried out in correspondence, which lasted until the poet’s death in December 1926.

The 1920s was the time when Mela Muter reached the heights of her artistic career. She was one of the most respected and financially stable artists in Paris. Her speciality was portraits. Mainly the famous and wealthy sat for her, such as the composers Albert Roussel, Edgar Varèse, Arthur Honegger and Maurice Ravel, and the writers Romain Rolland, Anatol France, Paul Valéry, Henryk Sienkiewicz and Stefan Żeromski. The dancer Serge Lifar, Ambassador of China Hoo-Wei-Teh, Hungarian President Mihály Károlyi, and the nephew of the great Rabindranath Tagore were also immortalized in Mela’s pictures.

In 1927, Muter received French citizenship and was allowed to become a member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. A year later, she moved into her own villa at 114 Bis Rue de Vaugirard in Montparnasse, designed for her by the famous architect Auguste Perret.

The Great Depression of the 1930s arrested the impetus of the avant-garde art movements from the early 20th century. All across Europe, new political groups were popping up. The high demand for art was no more. Mela Muter’s art, too, was not as popular as in the previous decade. However, she still exhibited in the Polish pavilion as part of the XVIII Biennale in Venice in 1933. In 1937, during the Parisian World Expo, she received the gold medal for her portrait of the nephew of Rabindranath Tagore. But it wasn’t enough for the upkeep of the villa at Rue de Vaugirard. Mela was forced to rent it out to cope with the debt she got into while building it. To make matters worse, in the last year of this ill-fated decade, World War II broke out.

In June 1940, Paris fell into the hands of the Nazis. France was divided into an occupied zone and the Vichy state in the south. Mela, like many residents of Jewish origins in Paris, went southwards in search of a safe place. Supporting herself by teaching painting and art history at the College Saint-Marie in Avignon, she survived until the liberation of France in 1945. In the meantime, the painter Jean Dubuffet moved into her villa in Paris. Despite the extensive efforts of Mela’s lawyers, she never managed to get her home back.

Upon her return to Paris, she rented increasingly inexpensive and therefore lowly flats, despite the fact that Dubuffet regularly paid rent for her house. In 1958, when she was tracked down by Bolesław Nawrocki junior, she lived in dark lodgings by the gateway of the house at 40 Rue Pascal, which regularly flooded during more intensive rain. In the 1960s, she went through a small renaissance of her artistic activity. Between 1966 and 1967 she had individual exhibitions in the galleries of Paris, Cologne, Oslo, San Francisco and New York. She never visited Poland again, despite efforts undertaken to bring her there.

She died alone on 16th May 1967, at the age of 91.

Translated from the Polish by Anna Błasiak