Poland and the Czech Republic. Two neighbouring Central European countries, inhabited mostly by Slavs, both of which have become popular with British bachelor parties. But that’s where the similarities end, and a pair of important questions arise: Which Polish films make us lose our will to live? And which Czech productions restore our balance, give us new energy, and help us to embrace life anew?

5 Polish Films That Make You Lose Your Will to Live

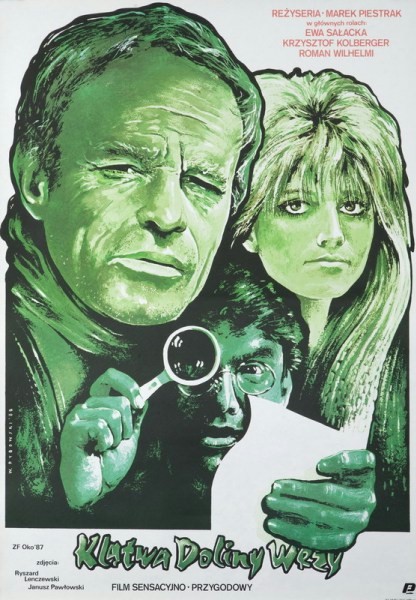

Curse of Snakes Valley

Marek Piestrak

They still haven’t come up with adjectives that can properly describe the story of Marek Piestrak and his film. Something that would be Poland’s answer to the adventures of Indiana Jones, recognized as the jewel in the crown of Polish B movies. On the same principles as we collect films like The Killer Shrews, Piestrak, just like Ed Wood, gained fame as the bard of bad taste, which unexpectedly became his greatest distinction and prize. Drawing 25 million people to cinemas for a story that occupies a position on the medal stand of the worst Polish films of all time, that make you lose the will to do anything at all: that’s a great artistic achievement.

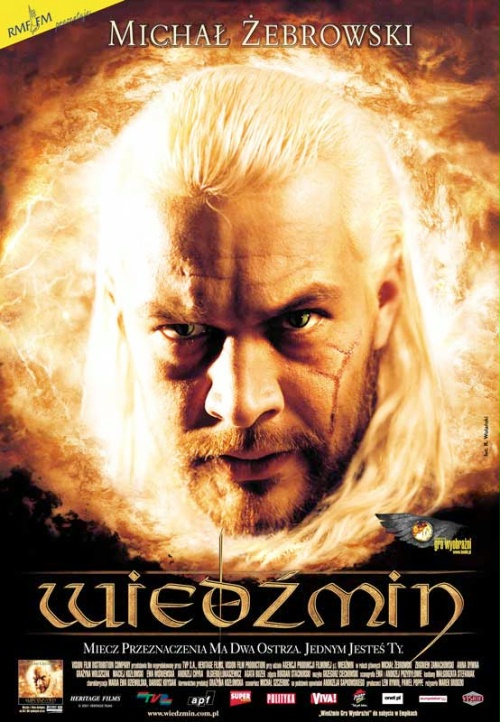

The Witcher

Marek Brodzki

Continuing down the path of films that are worse than the original and completely unsuccessful, the screen version of Andrzej Sapkowski’s cult novel also leaves a thick trail of stench. The fans who before the premiere founded the ‘Committee to Defend the One True Image of the Witcher’ also sparked a popular movement announcing an indefinite boycott of the production. They don’t like the screenplay or the leading actor; they don’t like the ineffective special effects or the rubber monsters. At the time, we all felt we had been made fools of; we expected something more than just another guilty pleasure, and the charms of getting to know a film so bad that you just have to shake your head. December saw the premiere of the new Witcher on Netflix. The entire nation held its breath.

Letters to Santa

Mitja Okorn

Or Poland’s answer to Richard Curtis’s Love Actually, one of the best holiday films ever made. Viewership in our country reaches into the millions, even though after the trail of saccharine sequels, stretching out like a tapeworm, the audience can barely breathe, and some have even faded away and no longer have the will to do anything at all thanks to the over-sweetening of this story. They say too many sweets isn’t healthy for you. Fortunately, the holidays are that magical time when nobody’s counting the empty calories they consume.

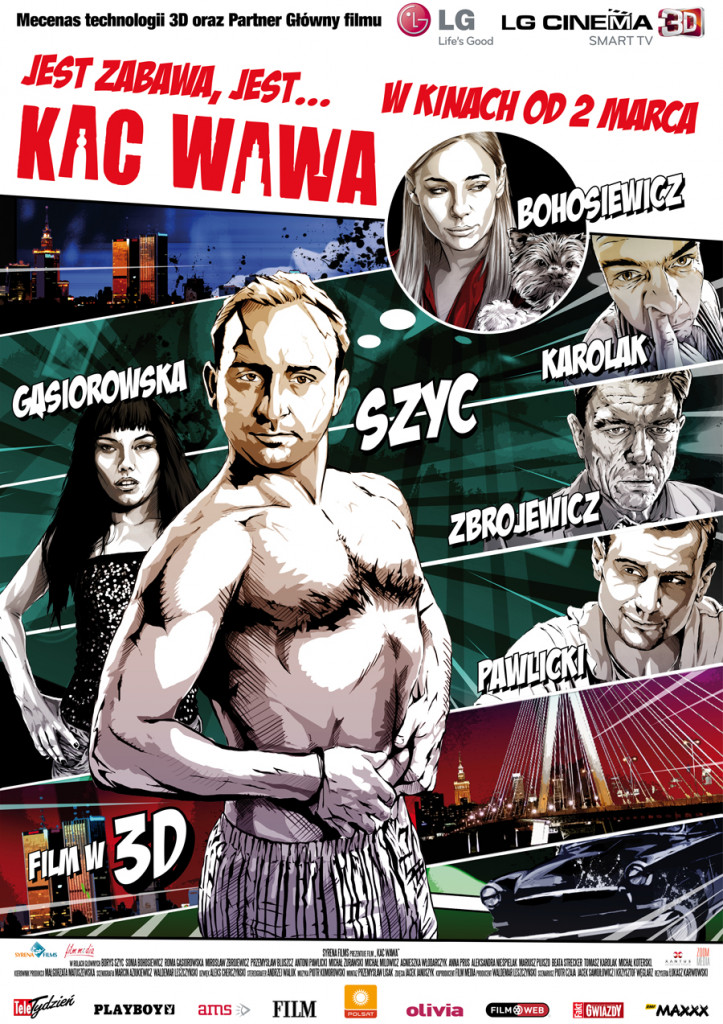

Kac Wawa

Łukasz Karwowski

“I left the cinema in a deep depression, silent as the grave and thinking up scenarios for how to finally end this cruel life,” said Krzysztof Varga, a well-known and talented film critic, after the premiere of another remake, this time a variation on the theme of The Hangover. The central theme chosen by the artists was a bout of diarrhoea suffered by one of the heroes of this story, which was created – in the words of the director, please note – “to show a naked lady with a big bust in 3D”. And so on, in the spirit of an incurably bad joke, which tragically has consequences and isn’t funny even for a fraction of a second. Go to the cinema on your own dime and at your own risk.

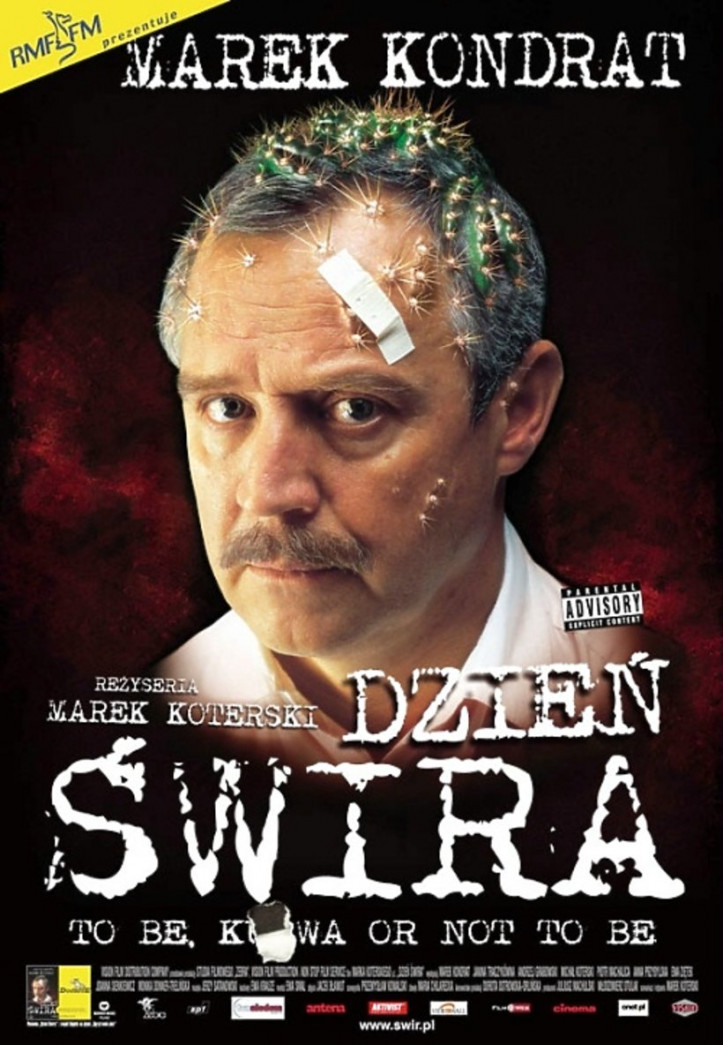

Day of the Wacko

Marek Koterski

For balance, a production whose vector of quality trends upward. We’re talking about Adaś Miałczyński: a member of the intelligentsia, a scholar of the Polish language, a Pole full of frustration and resentment against the world, who welcomes each day with the words: “Fuck, what a bunch of shit, fuck me.” After the premiere they called it “the funniest post-1989 Polish comedy”, because the hero’s phobias and the caricature of society shown in the film set off gales of laughter among its viewers. But Day of the Wacko only seems funny at first, and not necessarily later. It’s deceptive; it hurt then and it hurts today; it’s one of the saddest and most overwhelming experiences in the life of the Polish viewer. Often recommended to put the finishing touch on Blue Monday – the third Monday in January, also known as the most depressing day of the year.

5 Czech Films That Will Help You Embrace Life Anew

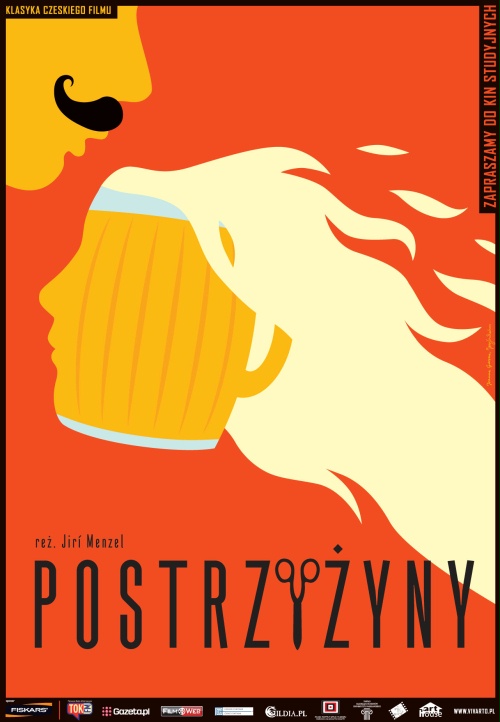

Cutting It Short

Jiří Menzel

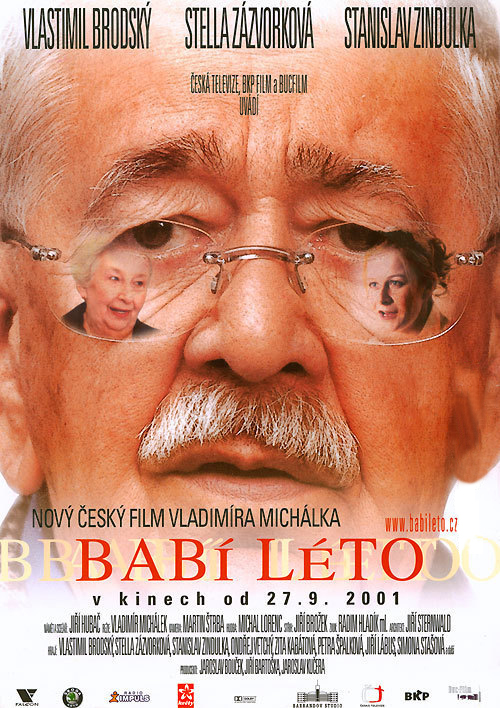

“Autumn Spring”, directed by Vladimír Michálek

Supposedly no surprise, and no big deal. Supposedly honest and not particularly original – an adaptation of Bohumil Hrabal and a film about what life is, meaning nothing special. About breathing, brewing beer and drinking that beer on a summer afternoon. About climbing up the chimney that rises over the local brewery, from which you can reach the sky, and about the titular haircutting. About a return to our beginnings; to an intimate, Arcadian, idyllic land, and breaking away from the uninteresting contemporary world. In a small Czech town, nothing happens. Time moves slowly and peacefully; it can’t disturb this idyll. After Menzel’s film, it’s best to get out of the city – and see for yourself!

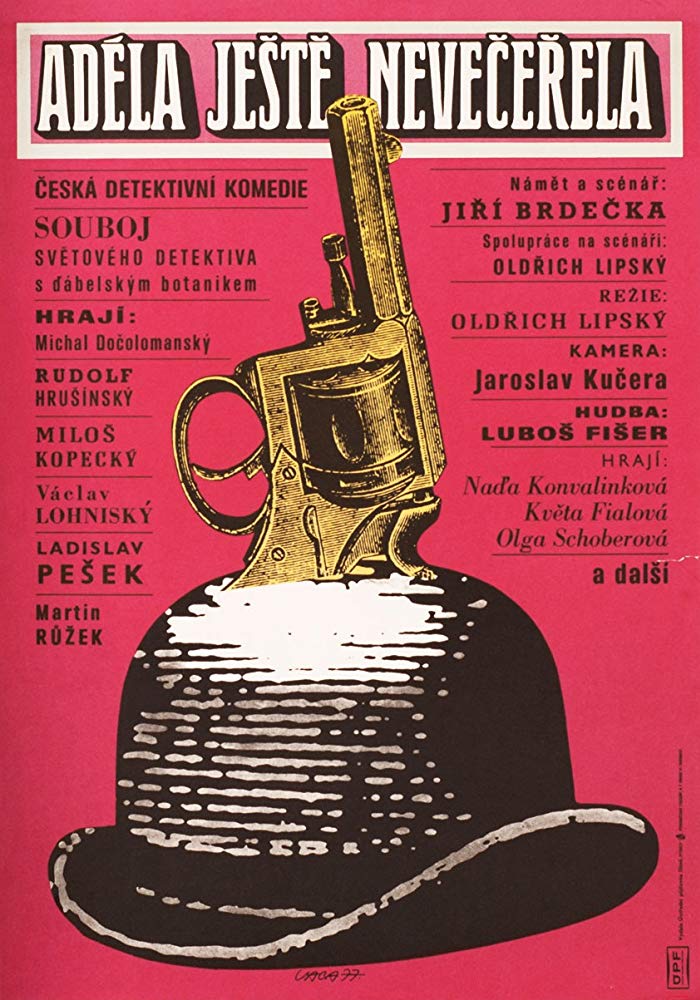

Dinner for Adele

Oldřich Lipský

A parody of American crime films, which gives nothing away to the best titles from the ZAZ (Zucker, Abrahams, Zucker) stable, such as Top Secret, The Naked Gun and Hot Shots! A famous detective arrives in Prague to unravel the mystery of the disappearance of a certain aristocratic lady’s dog, and to uncover the secret of a carnivorous plant. The hero squares off against the greatest criminal of the 20th century: a gardener with a magic flute, while in the meantime falling in love with frothy Pilsner. Well, you tell me: who else could think all this up?

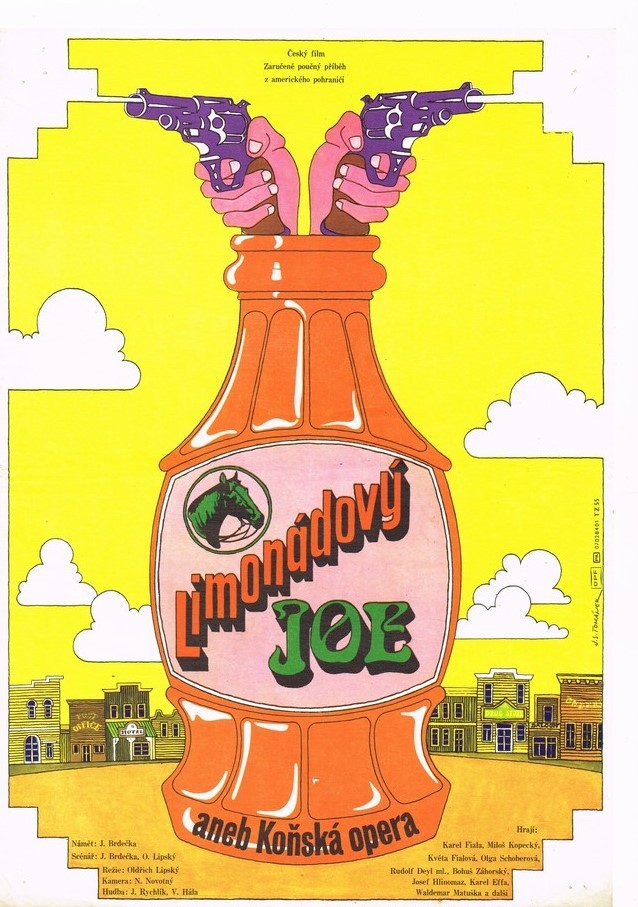

Lemonade Joe, or the Horse Opera

Oldřich Lipský

Sticking with Lipský: a knedle Western about a legendary gunslinger (“nejslavnejsi pistolnik Divokeho Zapadu”) who in Stetson City, in the drunken Wild West, promotes the alcohol-free soft drink ‘Kolaloka’ and the benefits that flow from prohibition. “This is a film that’s as strange, comical and unrelated to anything as only a Czech film can be,” is supposedly a quote from Karel Gott, who created the screenplay and was known as the Czech Presley and Pavarotti rolled into one. To be honest, I sign off on this statement wholeheartedly. Even in your wildest dreams, you can’t imagine what’s waiting for you once you end up inside the head of Oldřich Lipský.

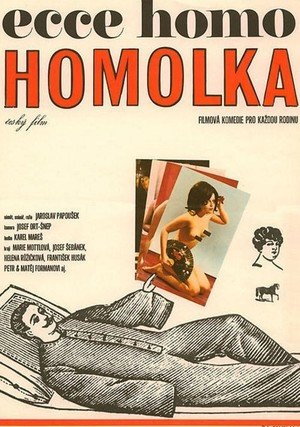

Behold Homolka

Jaroslav Papoušek

How to survive Sundays without a television – a story about a technological malfunction that could shake the foundations of the world. Czech humour in a nutshell, and the first of three cult films about the meandering of Prague’s Homolka family. I know people who say Grandpa Homolka and Al Bundy are the same person.

Autumn Spring

Vladimír Michálek

“More life!” 75-year-old František keeps telling himself as he moves inexorably to the end of his days. He doesn’t want to just wait passively, complain, set aside money for the funeral and sit whole days by the window waiting for the Grim Reaper to appear. Rather than giving in to boredom, he looks for small joys everywhere, and simple signs of life. “A mood of enthusiasm, silliness and small bouts of everyday madness are a self-reinforcing drive,” the hero seems to be saying to us. A hilarious, good-natured and heart-warming story. Just the right effect for a cold winter evening.

Translated from the Polish by Nathaniel Espino