I would like the reality before and after my exhibition to be different, to shift the viewer’s perspective. This is the essence of art, says photographer Wojtek Wieteska.

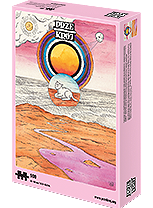

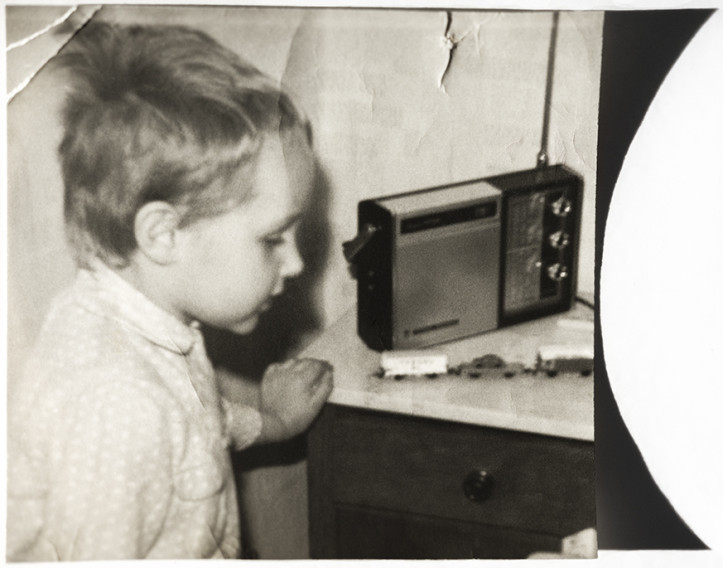

Aleksander Hudzik: You have placed a small photo on the table. In it I can see a kid who seems to be having a good time. Can you tell me what I’m looking at?

Wojtek Wieteska: This is the only photograph from Berlin that I have. It was taken by my dad on November 24, 1969. This boy is me. It’s my birthday, I’m looking at a miniature electric train, a toy I got as a gift.

How did you end up in Berlin in 1969?

My dad was contracted to East Berlin as a chef. He worked at the Café Warschau. It was a strange place, only years later I found out that American intelligence agents met there. We lived at Gartenstrasse 26, fifty yards from the Berlin Wall. At the time, the tenement served as a long-term hotel. We lived in one room, and from the window I could see a little bit of West Berlin.

Why are these memories so important to you?

Because they are my first memories, they are visual, and they contain what I work with today. It is because of them that I have retained these moving black-and-white postcards in my memory.

Did I hear correctly: black-and-white memories?

Yes, because that reality was gray. The only color I remember are red apples for Christmas, covered in transparent red icing. When I bit into them, the shell of crystalline icing cracked under my teeth, and then soft flesh. This was the first sensual experience I remember.

What was your childhood like in Berlin?

Berlin was still destroyed after the war. There was emptiness next to one preserved tenement house. We would run there with our friends, these spaces were our backyards. I also remember the shots fired at night; it was a heated period. However, memories of simple happiness prevail. For example, when I took my peers from Germany for dessert. At the Café Warschau, my mother served them ice cream and I became an important figure. I already spoke a little German. I also remember the feel of the suede of the Bavarian shorts I wore and the first film in the Kosmos cinema: Pan Wołodyjowski [Colonel Wolodyjowski]. But my main memory is the sensation of light, in every form, as a separate entity, as a shape, or when it fell through the window into the room in the afternoon. I remember looking through my fingers at the sun, the one that only shines over Berlin.

Was there a different light than in Poland?

Yes. In Berlin, especially in winter, the clouds are thick; suddenly they spread apart and the sun spills out. For a moment. In January this year I photographed them, which will be part of the exhibition.

Have you ever wondered how different your life would have been if you had stayed in Berlin?

My parents, whom I interviewed about their memories especially for the exhibition, told me: “We had to go back because you started school, otherwise you would have had to go to a German school.” I replied “Maybe that wouldn’t have been so bad after all?”

Yet the return to Poland made you leave for Paris.

And I spent ten years there, before 1989. It was my next incarnation, but that’s a topic for a different exhibition.

Tell us about the exhibition From One Photo, which we will soon see at the Polish Institute in Berlin.

I’ve been thinking about it since 2008. My partner at the time was looking for a property in Berlin, we went there with my son and looked at apartments. Then I remembered that I had lived in Berlin. My parents remembered the address. When I went there, I saw that beyond the wall everything was the same. I felt in my body that I was in a place I knew. That’s where it started.

So how did the story that began with a childhood memory develop?

I felt that Berlin was a special point on the map of my life. Every time I was in Berlin, I went to Gartenstrasse 26. I took pictures, I filmed. In January of this year, I photographed the route between the apartment and the restaurant that my parents used to drive along every day. These photographs will also be part of the exhibition.

You will bring not only photos but also furniture into the gallery.

A synthetic recreation of part of the room: a bed, a lamp, a cabinet, a window. I planned to live in the gallery for a week, but I will “only” stay for three days. Every day for eight hours I will be sitting on a mattress, playing with the electric train, and waiting for the audience. I will be looking for an answer to the main question of this exhibition.

What is that question?

I’m interested in this one photograph and one question that will be stuck on the gallery wall: “Can we see everything anew in one photograph?” This is an exhibition about the child everyone has in themselves. Mine is half a century away, I have gained distance from it, I can make an exhibition out of this personal tissue, start a journey back in time, think about where I am and where to go next.

And what can the audience think about?

Well, about the same thing as me! For me, this is a very easy exhibition to read. When you visit it, you will “enter through the gate of the tenement house at Gartenstrasse 26” because the gallery windows will be covered in photographs: you will see the main photo and the camera with which it was taken. You will read the question, listen to the interview, spend a moment with the electric train going in circles, with thoughts spinning. “What photo is important to you?”, “What photo do you connect your first memories with?”, “Where are you today?”, “Can you go back to the time of your innocence?” Personally, I really want to do it. Art can also be for just that.

Why do you want to return to innocence?

I want to go back in time, erasing—in the Bernhardian style—a few beaten paths along the way. Photos release memories, like Proust’s famous madeleine cake. Some time ago, during the divorce, my wife had her childhood photos spread out on the table. I understood that she was looking for support in her identity. It’s a natural reflex when a big change comes. You refer to something that was happy, the first, the beginning.

Are you going through a time of change now?

All my exhibitions since the 2000s have been connected with separating from my partners. I recently said to myself, “You’re tired of this pattern. You want an exhibition that reverses this process, one in which you will feel fully happy, and which will transport you into a new space-time.” And that’s why I went back fifty years. If you seek happiness, it is only in yourself, where happiness was at its purest.

Do you feel that an exhibition, or more broadly, art, can make one happy?

Yes! I believe that imagination allows you to create reality. If more people were involved in art, we would be much happier, because art says in an uncomplicated way that sometimes it is enough to think about something to start the process that makes it possible. I had a dream that I was by the sea, on the beach, but the sea was immediately a hundred miles from the shore—a dense, deep blue mass of moving waves. There were twenty opera singers on the beach. They went into the water, swam quite far away, and sang their arias there. I stood on the shore and watched. Next to me was an opera producer. I asked him, “What am I supposed to direct when they’re all drifting off and singing so far away?” I woke up and thought I was awaiting quite an adventure: a big wave that moves in front of me in slow motion. What does it mean in reality?

Did you find the answer?

The answer came to me from an old friend in California. I immediately bought a plane ticket: on March 12, I am flying to Los Angeles. I’ll be in Santa Monica for a month. On the hills. From there, you can see the entire city of LA. At night, it looks as if you were holding a glowing galaxy in your hand. This is how my construction process begins.

What happened that you needed a change?

I think it’s because of the separation from my last partner. It happened in New York. I felt like a wire sculpture by Alexander Calder: just the contour and nothing inside. I was walking around Manhattan, it was a beautiful spring, and I didn’t know what to do with myself. Everything and everyone flew through me. Fortunately, in a reflexive attempt to maintain a sense of reality, I filmed a lot, but I did not see the point of my work. At some point I realized that I needed people! To fill me with their stories. I came up with the question: “What will New York look like in one hundred years?” New Yorkers told me about the future, but these stories are also about them in the here and now.

What was it like working on the project?

Over six months, I filmed 120 conversations. These meetings reconstructed me. I experienced the moments I wanted. For the first time, I was happy to be alone! That I can fall in love three times a day because there are so many beautiful faces in New York. That I can create stories the way I like: from a consciously-planned coincidence.

I will tell you about one of them. Michele was older than me. We met at a party, on the roof of the MET. She was wearing a baseball cap and Nike shoes and was jumping to the music played by a DJ. I interviewed her, but it was a beautiful sunset and I got lost in filming. I invited her to the cinema, to an outdoor show in the MoMA garden. She said, “You’re lucky, this is my first vacation in the city.” She is a native resident of Manhattan. She came wearing an elegant satin, flared skirt and a necklace of copper safety pins in the ancient Egyptian style. After the film there was: a downpour, a broken umbrella, a borrowed jacket, the last coffee in an about-to-close Starbucks, the end of a downpour, and the fog of a hot, steaming pavement. The midtown became empty. It was just us. I didn’t know how old I was. She showed me storefronts that used to be bookstores. And she said she was the guardian angel of my project. A few days later, we recorded a conversation in Bryant Park. At the end, she said she couldn’t wait to see what it would be like in one hundred years! This year, she was the first to call me with New Year’s wishes.

Another time, I met a fourth-year student of film directing at the New York University. Kirill was surprised that I was filming everything with my hand. I told him that these vibrations and errors resulting from emotions were like a brushstroke, that it was my handwriting. “I’ll write it down, no one has told me that yet,” he replied. I was a lecturer at a film school and I know that school teaches students to unlearn these authentic gestures. Now I’ve made a film where I’ve made so many mistakes that they would kick me out of school for it, but I’m constructing my language out of them.

Are you against schools?

No, but I learned photography over two weeks in Paris when I was studying art history. In film school, I didn’t learn anything new across five years. Cinematography, yes, I got to know the tools of filming and editing; I know what space-time and rhythm are. But I didn’t like school because I felt misunderstood. I liked different cinema from the lecturers, different art; I was from a different planet, the French one—influenced by the new wave, formally promiscuous, and posing existential questions about the surrounding reality. I don’t have the best memories about studying itself, but film school was an oasis of freedom. Maybe this is what it is about, that freedom in school is the most important, and what professors require and whether these requirements can be met is a secondary matter.

Let’s return to New York.

In Washington Square, I met a man who was sunbathing with a large silver tray reflecting the sun. I asked if he would allow me to film him. He said yes, but I had to pay him five dollars. I made an exception and paid him. He said just a few words: that he has been coming here every day for forty years and that every time it is different. It will also be different in one hundred years. That’s it. As I was leaving, he asked me why I was even doing this. I replied that it was to get rid of my ego. This was the first time I said it out loud. An understanding flashed between us. I had the camera on all the time. It cost me five bucks to get the ego out!

Why should an artist get rid of the ego?

In the case of my New York project: to let others express themselves. And as for the Berlin project: to show that the artist is only an intermediary, a medium through which something (someone) speaks beyond. Therefore, the more open and incomplete I am, the more images can flow through me: I have room within me for a new message. A lack of ego means a wider frequency of transmission, more lanes on the highway.

Right now, I am only interested in what’s good for me: places, people. Without falsehood and hypocrisy. I put intuition and experience in the foreground. No distractions. Minimalism of means and tools of work. Time, peace, silence, sky, and clouds to dream creatively. That is, work and work again.

So today do you look differently at art in general?

Yes, I only see what I want to look at. And because I know what I like, I only see the art that speaks to me in a language I understand and love.

I wonder if what you experienced in New York has changed the way you look at the child we see in front of us in the photograph—how you look at the you from years ago?

If you live in only one time, the present, your imagination has limits, and all borders and walls are dangerous because they restrict the freedom of exchanging thoughts and movement. The fact that I experienced the Berlin Wall as a five-year-old is the basis of my independence. Both in personal and artistic life. I don’t believe in the institution of marriage and in the category of style. Style is a closed and finite form; it does not develop. I prefer to be and live in three times simultaneously. Berlin is the past, New York is the future, in the middle is the present and our conversation.

In January this year I was in the room at Gartenstrasse 26. Today it is an apartment. The owner let me in. I stood by the window; it was a gray day. I felt the same light as before, and for two seconds I felt as innocent as I did then. And because of those two seconds which stretch the time, everything makes sense.

The exhibition “From One Photograph” runs from March 3 to April 28, 2023 at the Polish Institute in Berlin, Germany.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Wojtek Wieteska

Photographer, cinematographer, and film director. He studied art history at the Paris-Sorbonne University and at the University of Warsaw, and also graduated from the Cinematography Department at the Film School in Łódź. He defended his doctorate in 2015. Lecturer with twenty years of experience.

He photographs, films, and writes about art. He creates exhibitions and photo books. Star sign: Sagittarius.

Translated from the Polish by Agata Masłowska