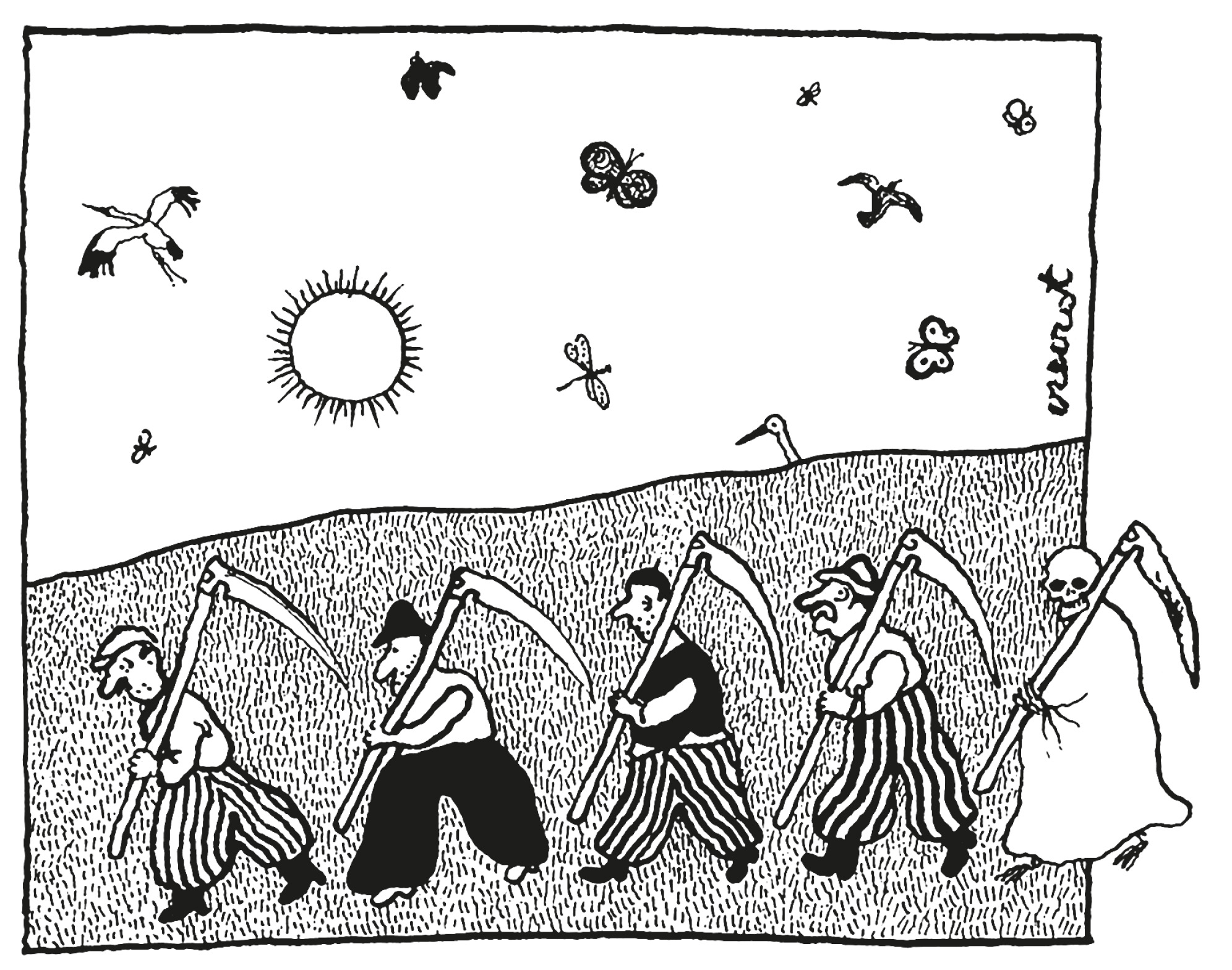

When we arrive in Pokrzydowo, at the farm of Aleksandra and Mieczysław Babalski, it’s early afternoon. There’s no sun, and it’s cold. This is normal enough, as it’s January. I regret slightly that we didn’t come at another time of year. Then maybe I would have enjoyed some fresh fruit and smelled the scent of grass.

But for now, it’s just grey and cold.

I still don’t know how wrong I am.

1.

“The mill’s not working today,” says a smiling Mieczysław when we arrive.

“What happened?”

“Oh, nothing, the stones have gotten dull, we need to sharpen them. Our son’s already working on it. Come in.”

In the storehouse we pass gigantic sacks full of grain.

“In a thirty-kilometre radius, there are about one hundred organic farmers. This grain is actually from them. We’ll use it to make flour, pasta, cereal.”

“But you also raise crops?”

“Of course. And in addition, we breed from the gene bank. The Plant Breeding and Acclimatization Institute is in Radzików (near Warsaw) and that’s where you can find Poland’s largest gene bank. They keep old species and varieties of grains. So that they don’t lose the ability to sprout, they have to be sown every twenty years. Almost thirty years ago, they started sowing them here – we have fifty spring plots and fifty winter ones. When we see that something’s growing well on one of those plots, we can take a hundred seeds from it, meaning four ears. They harvest the rest, and take it back to the bank in storage jars. From these four ears, after five years I have a hectare. That is, if the mice don’t eat it. This equates to about three hundred kilograms of seeds. Then I give them to other organic farmers – this one for half a hectare, another for half a hectare. No, I don’t sell them. I just subtract what I gave them when they bring me the sacks of grain that you see, and I pay for the rest. Oh, here, for example, you have einkorn – a wild form of wheat, the most expensive. It’s the finest and it yields poorly, but the price is good – it gets up to seven thousand złotys [around £1400] a tonne. Here we have emmer and spelt, also species of wheat. Like einkorn, they’re different from ordinary wheat in that they’re hulled.”

“Hulled?”

“The grain sits in the hull, meaning the chaff. Later, farmers take this chaff for animal feed. And here’s some barley, ready to be processed. The whole grain is shelled and polished, making it cereal barley. You can also cut it, and then it’s village-style cereal. Or soak it, and make flakes. Oh, look, here’s some spring rye.”

Mieczysław takes some grains into his hands and sniffs.

“This rye has to be burned!” he tells a worker. “Here, smell – what a